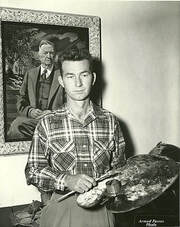

When I was a kid, I had a cousin named Cézanne who would babysit me and my brothers. She was named after the French Impressionist, Paul Cézanne. She has two brothers who are also named after historical artists. They are Michelangelo (or Michael), and Rembrandt (nicknamed Rem). Their father was Sam Smith who was married to my maternal great aunt, Harriet Holley Hening. I have only scattered memories about my aunt, uncle, and cousins but I was reminded of them when my dad told me that Sam had been the head of the art department at the University of New Mexico. I was intrigued and wanted to learn more about him. I learned that my uncle Sam was an accomplished painter, draftsperson, printmaker, and was a professor of fine art. In fact, he was revered as one of the most accomplished Albuquerque painters during the 20th century. What is truly inspiring is that Sam dropped out of school at age 13. He never received a high school diploma, nor a college degree, yet he rose to the level of college professor at an acclaimed university. He was not the head of the art department, but the accomplishment is remarkable, nevertheless. Sam Smith was born in Thorndale, Texas in 1918. In 1925, when he was 7 years old, his family moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico. After dropping out of high school, he began to apprentice himself to artists in the area. He studied with artists Randall Davey, Jack Levine, Ben Turner, and Carl Von Hassler. It is rumored that he spent some time with Nicolai Fechin, but I cannot confirm that. He was good friends with Wilson Hurley, who praised his talent and wrote, “Sam bloomed early. He was extremely prolific right at the end of the war...Sam had done a bunch of paintings of China, and they were gorgeous... Everybody was excited with the work he was doing. He was friendly, telling me what he was trying to do and why. I was like a little brother." ~ Wilson Hurley In 1941 Sam enlisted in the US Army. While in bootcamp, he volunteered to paint a patriotic mural of Texas over the camp service club entrance. His talents were noticed and earned him orders to serve as an Army Combat Artist. He served our nation by sketching and painting combat scenes in the China-Myanmar Indian Theater and in West Africa. I would love to see those sketches and the paintings of China mentioned in Hurley’s quote. They are located at the Pentagon but are not available to view online. After the war, Sam returned to New Mexico and married my aunt, and in 1950 he went to work at the College of Fine Arts at UNM to begin a teaching career. He taught watercolor and oil painting and retired in 1986. While searching for information, I discovered a children’s book that Sam had illustrated. It is entitled, “The Cowboy’s Christmas Tree,” by Effie Paige Eddy. I have a copy of the book and if I recall, it is signed by the artist and was a gift to me and my brothers. I am excited about learning more about my uncle and to share this story with you. It feels poignant to learn about him while I prepare for a new path studying at the College of Fine Arts where he taught. I am inspired by the opportunity to study there and in the coming year, I plan to reach out to my cousins. I’d like to reconnect, and perhaps they have copies or even the original combat sketches from WWII! Have a Happy New Year Everyone! Notes: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sam_Smith_(painter0) https://www.adobegallery.com/artist/Samuel_Smith_1918_1999178733157

0 Comments

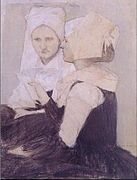

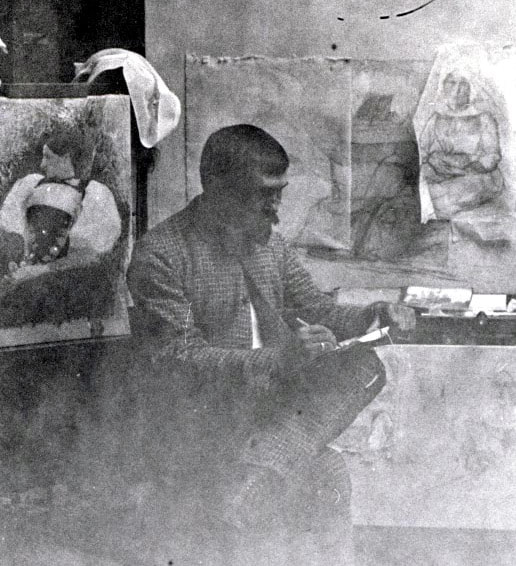

"Les Bretonnes au Pardon" ("Breton Women at a Pardon"), 1887. Oil on Canvas. Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon. Pascal-Adolphe-Jean Dagnan-Bouveret was a nineteenth century French painter. He was a gifted and favorite student of Jean Léon Gérôme at the École des Beaux-Art, the preeminent art academy in Paris, where those who entered were selected to have an official career as a painter. He began his studies in April of 1869. In his youth, Bouveret and his brothers lived with their grandparents in Mulen, France, after their mothers death in 1858. Only a year before her death, Louise Bouveret moved her sons, Pascal-Adolphe-Jean and Emile Gabriel to Rio de Janeiro, joining their father, Bernard Dagnan, where he owned a prosperous clothing company. After his mother died, his father sent his children (including a third son, Victor), back to France to live with his father-in-law, Gabriel Bouveret. The young artist and his brothers grew up in a comfortable middle-class environment and it was there where he began to develop his artistic sense. He took art lessons as a child in Mulen and made many drawings of his family. It was a turbulent time in France when Dagnan-Bouveret was a student at the École. The Franco Prussian War of 1870 had taken a devastating toll on the country and because of the fighting in the Paris Commune, large areas of Paris were destroyed. As a result, the supremacy of the arts in France began to falter. But by the end of the decade France began to see a return of the artistic spirit and young artists from all around Europe and the United States came to Paris to study at the école. These students believed that they could receive the best education from the traditional academies in Paris and that academic training would position them for exposure through exhibiting in the Salons. Dagnan-Bouveret enjoyed success as a young artist in Paris, winning numerous prizes at the Salon. He began to see the need to shift to the more modern and contemporary painting styles becoming fashionable during the late nineteenth century and he was capable of transforming his classical academic training into new methods so that his work was available to the public. In fact, Dagnan-Bouveret, like many other artists began to explore the use of photography and was interested in how the new medium could aide the artist in an academic naturalistic approach. His teacher, Jean Léon Gérôme used photography as well. “His insistence on using photography under the initial stimulus of Gérôme, reveals that he was among the most forward-looking members of the academic tradition; he recognized that the “old" classical system of planning a composition had to respond to the new technologies that were already being applied and assimilated by painters of the avant-garde."(1) The images above represent a sampling of photos and sketches Dagnan-Bouveret made in preparation for “Les Bretonnes au Pardon" (“Breton Women at a Pardon") - shown above. He began to make this painting in the summer of 1887 while in Ormoy, France. He had taken a photograph of a church in the distance and pictured in the foreground of the photo is a male figure with a handkerchief on his head - the same location where one of the Breton women sits in the final painting. Dagnan-Bouveret worked in an outdoor tent where he compiled numerous preliminary drawings on tracing paper, pastel drawings, and oil sketches. He made drawings on tracing paper so they might be modified and enlarged for the final composition. Photographer unknown, Dagnan-Bouveret Working on Tracing Drawings for “Breton Women at a Pardon." ca. 1887, Archives Départmentales de la Houte-Saône, Vesoul. The Breton people come from Brittany, one of the most staunchly Roman Catholic regions of France. The Breton's are, along with the Welch and Cornish, one of the last vestiges of the ancient British. Dagnan-Bouveret's painting was completed in late 1888 or 1889, the same year it was exhibited at the Salon. It received the Medal of Honor at the Salon and the Grand Prize at the Exposition Universalle. The public reception of the painting was overwhelming. A very influential critic at the time, Albert Wolff, hailed the Breton Women as “a work of beauty, contemplation, and peacefulness. It is great, honest art."(2)

During the early twentieth century, most traditionalist painters became obscure and outdated. Although he continued to paint actively into the second and third decades of the twentieth century, Dagnan-Bouveret's traditional work was considered passé and insignificant as compared to the new artists who were painting under the auspices of surrealism, dadaism, fauvism and the School of Paris. One year after the artist's death, in 1930, a retrospective of his work was held at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. By then avant-garde modernism had progressed and dominated the art scene in Paris and abroad and the French academic style of painting was effectively over, due to the unilateral control of the academic professors of the Ecole who were resistant to change and modern approaches to painting. From 1930 - 1980 little attention was paid to Pascal Adolphe Jean Dagnan-Bouveret. His work, along with other French academic painters, like Jean Léon Gérôme, William Bouguereau and Jules Breton were forgotten after their deaths. Dagnan-Bouveret worked as an advocate for the preservation of tradition and while he came against the avant-garde, he understood and even embraced modernism. From 1930 - 1980 little attention was paid to Pascal Adolphe Jean Dagnan-Bouveret. His work, along with other French academic painters, like Jean Léon Gérôme, William Bouguereau and Jules Breton were forgotten after their deaths. Dagnan-Bouveret worked as an advocate for the preservation of tradition and while he came against the avant-garde, he understood and even embraced modernism. (1), (2)Gabriel P.Weisberg. Against the Modern: Dagnan-Bouveret and the Transformation of the Academic Tradition. New York: Dahesh Museum of Art, 2002. ISBN 0-8135-3156-X |

Leslie LienauSharing my thoughts and ideas mostly about art and art history. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed